ARTFRIEND: RETHINKING THE CURATION OF 'HOUSEWARMING'

- Agnès Houghton-Boyle

- Feb 19, 2024

- 4 min read

In an interview I conducted not so long ago with the filmmaker Rachel Garfield about her extensive career, she said that after leaving art school she had pledged never wait for someone else to give her the money or the ability to make work and asserted that artists can always find ways to produce and showcase their work independently. This sentiment is in some ways embodied by the gallerist and founder of ArtFriend, Shona Bland, who, after facing numerous rejections in her attempts to secure a job in the art world, decided to establish her own gallery. ArtFriend, set up in 2023 in East London, operates as a commercial gallery space with a mission to make art exhibition and acquisition accessible to a diverse audience. Bland describes it as a non-conventional, inclusive space, rejecting art jargon and welcoming everyone to the gallery.

Previous projects include the provocatively titled Rejects, an exhibition which showcased works which had not been selected for the 2023 Royal Academy Summer Exhibition. Pointedly hosted in a locale near the White Cube in Bermondsey, the exhibition foregrounded the artists’ experiences of rejection, which in some ways gives opportunity for a constructive dialogue about fostering a more nuanced understanding of inclusion and diversity in the art world. However, a detailed breakdown of the exhibited works or artists was unavailable online, suggesting that the common thread among them was solely their rejection rather than any specific contextual or thematic content.

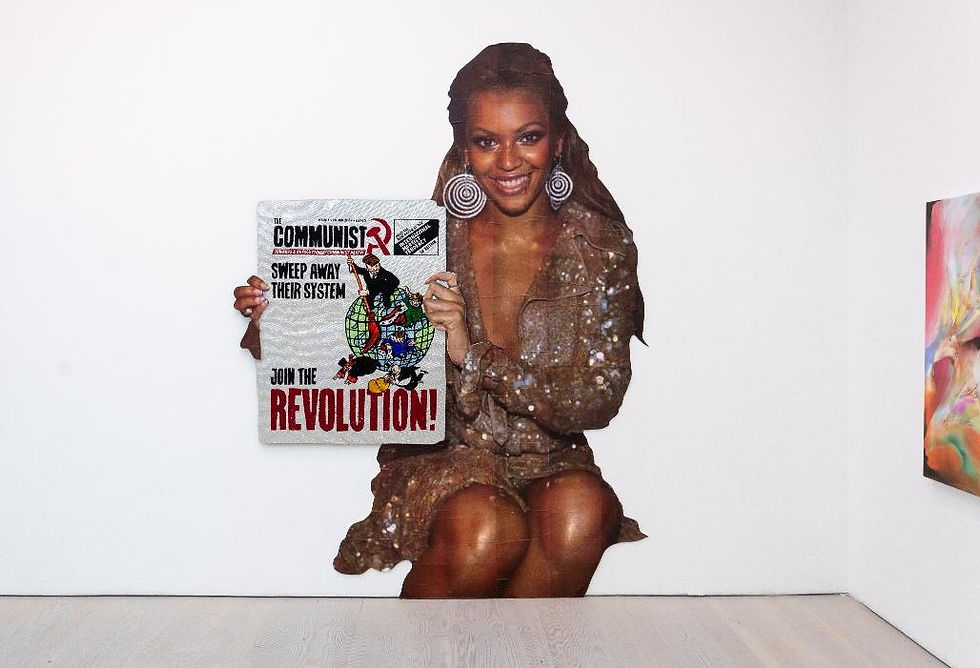

The curatorial stance is again the key feature of ArtFriend’s recent Housewarming event. The exhibition which closes at the end of the week, has transformed an acquaintance’s derelict property, in a Stoke Newington townhouse neighbourhood, into a two-week art installation. Prints from local alternative artists, which are hung alongside 1950s design features, in olive green carpeted and abstractly wall papered rooms, seamlessly blend with the space; kitschy illustrations and maps of cities, including London, with ‘London is always a good idea’ etc, lettered in gold, look as though they could have been hung by the previous inhabitants. The exhibition features a range of artists, including North London muralist Matt Dosa, known for his four-story mural in Wood Green. Dosa's art takes over an entire room showcasing rainbow stripes and a spray-painted blue bicycle. Another room features Craig Keenan's rich blue walls and cyanotypes capturing scenes of clouds, and Adam Bartlett's room at the top of the house is most impressive, featuring wide-eyed pink tigers and eclectic jungle scenes.

Photos: Agnes Houghton-Boyle

The thread that links the works seems to be their bold playfulness but again there is a notable lack of wall text or contextualising information about the artist’s practice or thematic choices. The framed pieces available for purchased focus on aesthetic appeal and are chosen specifically for domestic spaces, and in some ways the project has echoes of Charleston House, which the Bloomsbury group famously filled completely with decorative art and interesting objects. However, the notable lack of written information providing viewers with details about the artist’s and insights into the pieces directs attention away from content and towards the immersive experience, that supposedly aligns with the mission of breaking down traditional barriers to the art world’s gallery settings.

Photos: Agnes Houghton-Boyle

My concern lies with ArtFriend’s generalising critique of the art world, and of the term ‘art jargon,’ which it seems to answer by not only substituting technical expressions and terminology but language at all. It’s not as though the work in Housewarming necessarily seeks to unpick or undermine layers of art history, and certainly, there is a valid place for illustration and decorative art – after all, as the website notes, ‘everyone likes nice walls.’ But I find troubling the notion that broader audiences will not engage or fully comprehend with art because of its terms related to art history, artistic techniques, styles and critical theory. What’s more, we might question what is meant by their use of the term inclusivity? Inclusive to who, or of what? What efforts are being made to engage or represent individuals from various races, ethnicities, genders, ages, socioeconomic statuses, abilities etc?

I worry that what ArtFriend is really getting at here is the suggestion that the art world may be difficult for, to use the term loosely, working-class people to understand. The idea that, to working-class audiences, decorative, commercially-available art constitutes a more enjoyable viewing experience than fine art hardly challenges the art world’s barriers to entry in the way that ArtFriend intends to: rather, it perpetuates the idea that fine art is for a particular kind of person. You would not suggest that in order to enjoy football, one should have a background in premier league football. Like anything, there are dimensions to art. You cannot walk off the street and purport to be an engineer or a teacher. In the same way, an art’s background is key to curation. That is not to perpetuate the political or aesthetic angle of the artist as professional, but without application, art risks being trite.

Cover image: Dave Buonaguidi, Norf Sarf (2023)

Agnès Houghton-Boyle is a critic and programmer based in London. Her writing features in Talking Shorts Magazine and Fetch London.