ARS LUDICRA: OR, HOW TO TURN VIDEO GAMES INTO ART

- Victoria Comstock-Kershaw

- Dec 12, 2023

- 7 min read

Can video games be art? According to essayist and critic Robert Ebert, the answer is a resounding “no”. But pioneers of the video game poetry movement like C.A Knight are determined to prove him wrong. Ahead of his display at OUTPOST's December exhibition, the poet-cum-games-developer and creator of the Ars Ludicra project sits down with Fetch to discuss his first two collections, his love of the Game Boy Color, and his hopes for the future of video game poetry.

Tell us a bit about Ars Ludicra.

Ars Ludicra itself translates into “the art of the game”. It’s a riff on “ars poetica”, that every great poet gets to write one day. To get the name right we contacted Latin departments in universities across the UK. We got many emails telling us to never contact them again, but the University of St Andrew’s Latin department got back to us within 24 hours and were so helpful and ended up giving us the name.

Originally, the project was going to be one game; it was going to be a merge of poetry and Tetris, [but] it was way too hard at the time. I spent like, three or four months trying to figure it out, and then we had to pivot. But I’m lucky I had this idea, because that’s what led to Ars Ludicra as it is now.

There isn’t a ton of video game poetry out there.

The most honest I can be is that I have no idea what video game poetry is. I think that’s kind of the best part, that’s where the fun comes from: if you don’t have any idea what comes next and everything is just highly experimental all the time, then you don’t really put limits on yourself or what you think you should do. I often struggled with written word and the idea of what makes a good poem, because a lot of the stuff I wanted to do had already been done. I didn’t feel like it was good enough compared to what other people were doing, whereas with this - well, nobody else is doing it. There’s maybe three or four active video game poets, all of them doing different kinds of poetry for different kinds of consoles. I think I’m only one of two poets working on the Game Boy. There’s very few of us and none of us know what it is.

It’s such a unique format. What originally drew you to it?

It was interesting because I had gone from written poetry to visual poetry. The driving force was the idea that you play it, rather than just being an observer of art - rather than just looking at a painting or reading a poem, having that distance from it, I wanted to focus on the idea that with video game poetry, it’s your actions that mean the poem takes place. The poet gets to put the dominoes up, but you get to push them over. I love the kind of rawness in that - you can kind of blame the reader, in a way. That extra level of connection, that you can take everything from sound poetry, visual poetry, written poetry and combine them.

Why choose the Game Boy?

My first console was the Game Boy Color. The idea of having something portable, and something that is now largely on the internet as open source - you know, anyone can make anything for the Game Boy these days, and it’s all free. If you wanted to make something for the Nintendo Switch, for example, the loops you have to go through to even make something are big enough, but certifying it to even allow it to be played is even more money, time and connections… I just wanted something that was easily accessible. And the original Game Boy’s size is about the size of a chapbook [a small paper-covered booklet io poetry], so holding it is very reminiscent of reading traditional poetry.

Do you think that type of nostalgia is important to your work?

Yeah, it really felt at home in a really strange sense. Making poetry and trying to churn up emotions is a process, and having that connection to my Game Boy - it’s where I went to play Pokemon, Bugs Bunny, all this childhood stuff since I was very, very small - it felt so familiar, and I knew what I enjoyed and what made a good game. It felt a lot more ‘right’ than doing it for any other console. The Game Boy has been the most fun I’ve ever had making video game poetry, any other console I’ve tried working on has been - at best - a mess.

Yes - you’ve spoken about how, for example, S T A R G A Z E R S was a really daunting project. What’s the most challenging aspect of turning these poems into video games?

When it comes to translation work, the hardest part is making sure you’re making an ethical translation. Respecting the original author and what they made without just lifting their creation and turning it into something you’ve made is hard. One of the biggest things for Collection One was that I chose poets that were, by and large, already deceased. Because we didn’t really know how the copyright worked! And the art world can be quite generous, but if I chose the one poet who really didn’t like [video game poetry], you know, what would happen? So a lot of translation work is trying to be respectful but also transformative, and that wasn’t easy.

As for the original pieces, my experience has been different. At the time, I was looking back at my old work and thinking about what I remarked as being my own success. There’s a very limited number of pieces that I can go back and feel comfortable reading and S t a r g a z e r, the original poem, is one of them. I was comfortable with it, I didn’t go back and edit it when I finished it, I thought “this is my best one”. I found it again and the shocking thing was I read it completely differently than when I had written it; I did not associate the poem at all with what had spawned it when I wrote it. To me, I wasn’t the author anymore. Discovering this new reading, this new meaning of it was a difficult day. And the thought process was, well I’m already doing this project where I translate poems - so what can I do with this?

Do you write your original pieces knowing that you’re going to make them into a video game, or is it a parallel process?

I have attempted that. But I think I started off on the right foot making translations originally, because there’s nothing out there to tell you how to make video game poetry. I did so much research but I was flying blind for the entirety of Collection One; I still am for Collection Two. What I learned from Collection One was how to make a connection with imagery and emotion, the best way to display that, whether it’s audio or the tactile feel of the buttons - we don’t use taste yet, but four out of the five senses are being engaged.

I’m going to lick the Game Boy.

Please don’t. It's from the nineties.

So am I.

Okay.

What do you feel video games can achieve that traditional poetry can’t?

It’s kind of a different thinking process; with written poetry it’s all about words and metaphors, pentameters, all that kind of thing. With video games, it’s like - can I take stuff from Super Mario and make it more macabre? In the first piece of Collection Two, that whole level is lifted and transformed from Super Mario. It’s doing stuff like exploring the question, what can I do with a video that feels like the best way to communicate what I’m trying to do?

The second half of Collection Two has been so different from what I originally planned. You know what they say, “the most reliable part of a plan is that’s unreliable.” The first two pieces were extremely different - they shared some of the same DNA as what came out, but still different.

How else is Collection Two going to be different from Collection One? What should we be expecting?

More game than poem, at least on a surface level. One of the things I lament about Collection One is it felt more like a visual experience than an actual game. I was trying to find that balance but I don’t think I nailed it in Collection One. I want the new work to really be video game poetry, not just an experience: there needs to be an actual game to play. For example, in RUN!RUN!RUN, I had something very particular I wanted to convey but the game came first, which is the infinite runner [a subgenre of platform game in which the player character runs for an infinite amount of time while avoiding obstacles]. I spent weeks just trying to get the game right before I even touched the visual art or the text or the easter egg. I’m not actually too fond of Collection One anymore - it was once the best thing in my life, and now I’m like “eh”.

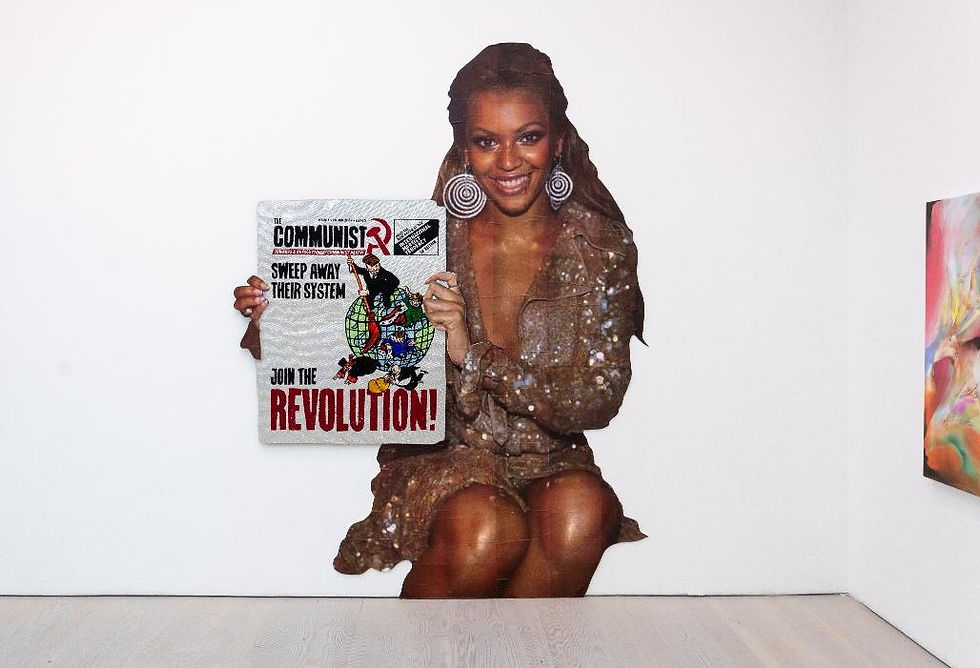

Tell me about the upcoming exhibition at OUTPOST.

I’m modifying my GameCube for it, because we want to do this whole thing with my old CRT television and put that on display with my new games for Collection Two and hopefully have handhelds that we can hand around. I’m super jazzed for it, it hasn’t really set in that I’m doing it yet - it’s the first time any of my work is going to be displayed outside of the website.

What are you hoping viewers are going to get out of the exhibition?

I haven’t thought too much about that. I’ll be buzzing around watching them play it - because, like I say, you can look up video game poetry on Google or Google Scholar and you can’t really find anything. So for me, of course I’m looking for viewers to get something out of it for themselves, but also I want to see how people interact with my work. That way I can see what's' working because so much of this is just throwing stuff at the wall and seeing what sticks. I need to understand “is there a general point where people are playing this and putting it down?”.

That's so interesting - you’re literally approaching this like a game developer. That’s the sort of thing devs look at when beta-testing. But it's not a video game - it’s still poetry. Where do you think a format like that is leading?

Video game poetry is such a new art, and actually I hope and pray that someday someone comes out of the woods and backhands me by creating a piece of video game poetry that's so much better than mine. For me, that’s the perfect outcome - if we can get it into the mainstream. It’s still early days. But I think everyone should try it at least once, every poet should do it, and they’ll see why I’m dedicating my career to it. It’s very, very fulfilling once you figure out what you’re trying to do.