REVIEW | THE NATIONAL PORTRAIT GALLERY IS IN PORTRAIT POVERTY

- Victoria Comstock-Kershaw

- Jun 25, 2023

- 6 min read

Updated: Jun 26, 2023

£41.3 million later and still no good portraits, writes Victoria Comstock-Kershaw.

The architectural facelift of the National Portrait Gallery itself is absolutely fine. Tracey Emin’s low-relief bronze panels of “everywoman” faces on the new doors are appropriately inoffensive. The wall colours are well chosen, the fonts are crisp and clean, and they have clearly taken a page out of Dulwich Picture Gallery’s book and ensured that there is enough space in front of every single painting in order to step back and avoid glare. The 50-lux lighting of photographs and sketches is particularly tasteful. Renovation efforts have set the gallery back a cool £41.3 million, headed by Jamie Fobert Architects, but there is nothing radical or even particular new about the space (a fact rather generously dubbed as an “anti-egotistical rejection of the yesteryear vogue for look-at-me ‘starchitecture’” by the Telegraph). This is far from a bad thing; I’m a firm believer in the idea that portrait galleries should remain uncomplicated, if only to give due credence to the complexity of their inhabitants.

The core of the problem is that the NPG simply doesn’t own very many good portraits. Sir Joshua Reynolds' Portrait of Mai (Omai) is a great example of this: acquired to great media fuss for £50 million, meticulously marketed as the ‘first British portrait of a person of colour’, hung centrally and squarely as the shining star of the ‘gawdy chaos’ of the Rage for Exhibitions room – and it’s simply dull. Reynolds had never been a master of composition and this has never been more evident in his rendition of the Polynesian royal attendant-cum-celebrity. He gestures haphazardly off-canvas in the style of the Apollo Beldevere, leaning on proportionally-incorrect legs, the colours reminiscent of a minimalist Scandinavian apartment; all beiges and browns. The placard in front of it carefully leaves out the fascinating story behind Mai’s ascent to celebrity, or the fact that Reynolds dressed him in Indian garb rather than Polynesian, or really any other pertinent information beyond his racial background and the substantial amount of donors that the work took to acquire.

From left to right: Portrait of Mai (Omai), Sir Joshua Reynolds, c. 1776, Christopher and Mary Ann Anstey, William Hoare (c. 1776), Thomas Hope, Sir William Beechey, (1798)

The truly spectacular works are few and far between, and the gallery does little to guide you to them. Many feel almost like accidental additions to the space – even within Omai’s room there are better, more interesting works tucked away: William Hoare’s deeply endearing Christopher and Mary Ann Anstey (c. 1776), depicting an exasperated father glancing pleadingly at the viewer as his daughter tries to distract him, or Sir William Beechey’s Thomas Hope (1798), a magnificent rendition of the eighteenth-century magnate in exotic garb with superb brushwork along the rising smoke of his pipe. There are several large-scale group portraits that work particularly well both curatorially and visually; The Somerset House Conference (1604) is a powerful depiction of the Anglo-Spanish War negotiations that spices up an otherwise rather dull Tudor portrait room, and the juxtaposition of Benjamin Robert Haydon’s The Anti-Slavery Society Convention (1841) and Sir George Hayter’s The House of Commons (1833-34) in the Radicals, Resistance and Reform collection present two intimidatingly good works that really heighten the atmosphere of societal change. But beyond a few other hidden gems scattered throughout the gallery – the unfinished and unrestored Bronte sisters’ portrait with the spooky outline of its painter emerging from the background, Hockney’s devastatingly cool Portrait of Sir David Webster (1971) or Paul Brason’s Conservative Party Conference (1982-85)– the overall quality is simply lacking.

The Kit-cat Club Portraits room, despite being one of the nicest spots in the gallery with its towering light-box dome, has been dedicated to portraits by Sir Godfrey Kneller and is therefore transformed into a deeply uninspiring space, smothering the viewer in a sea of samey 17th century faces in various silly wigs against mud-brown backgrounds. The Yevonde exhibit is just as repetitive and ugly; while the saccharine colours of her photographs may have held a certain allure during their own time, they now appear garish (especially against the snot-yellow walls of the second half of the exhibit), and presenting her work as ‘radical’ does not alter the inherent poor aesthetic quality. The collection dedicated to British writers is abysmally boring, filled with low-quality photographs and half-finished sketches (the sole likeness of Jane Austen is tucked away somewhere earlier in the gallery between some particularly gaudy miniatures). Even the 'cool-girl ceiling-smashers' collection dedicated to reframing women is severely lacking in technically impressive photographs, relying too heavily on the girl-power aspect to present any visually captivating work. There are too many ‘school of ’s and not enough ‘by ’s, too many unremarkable works by minor artists forgotten by art history for a reason.

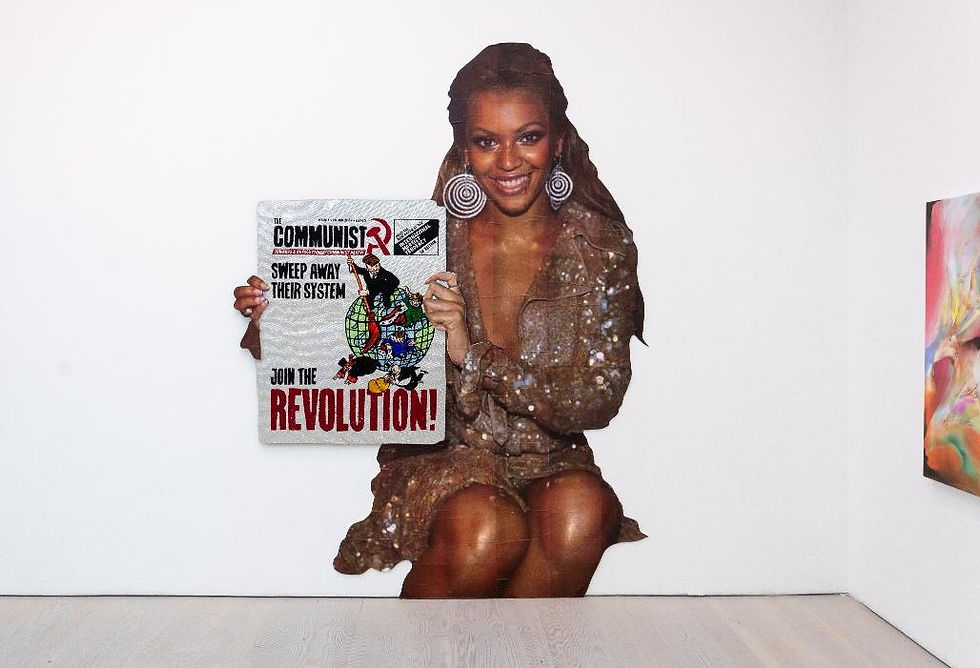

The modern artworks dotted throughout suffer from the same problem. I’m not inherently opposed to the inclusion of contemporary art in historical galleries, and in fact believe that when done well it can be a genuinely valuable addition to any museum – Linder’s collages alongside Duncan Grant at Charleston comes to mind, as does António Ole’s Township Wall at the Ethnologisches Museum in Berlin – but only when the artwork is good in and of itself. The freshly-generated dialogue between the work and its new context shouldn’t shoulder the entirety of the artistic conversation, but unfortunately it’s what has happened at the NPG. Especially egregious is Lubaina Himid’s Toussaint L’Ouverture (1987) sculpture, a collage portrait of the Haitian revolutionary on a slab of plywood composed of newspaper cuttings about racism in Britain during the 1980s. It’s an ugly, boorish work of art (a shame, as Himid has produced some rather fine watercolours that explore concepts of Black British identity far more succinctly), and its placement in the section of the gallery dedicated to colonisation and slavery sits somewhere in between the tokenistic (L’Ouverture freed a French, not a British, colony) and the ghoulish (there's a certain meanness in propping up the childishness of 1980s Neo-Expressionism next to the seriousness of eighteenth-century Portraiture).

Of course, I dread to imagine the meticulous discussion and time undertaken by whichever sensitivity readership commission was selected to write the new placards and posters, but the hours spent discussing whether to capitalise the 'w' in 'womyn' were not in vain. The gallery follows a perfectly respectable chronology from the Tudors to today, injected with smatterings of sections dedicated to various minorities. It’s much more tastefully done than other attempts at historicising art – see the Tate's catastrophically-received revisionist rehang – and while it doesn’t always enhance the experience, it doesn’t interrupt it. There are moments of genuine visual impressiveness, such as the Challenging Identities 1880–1914 collection with its charming lithographs of Indian socialites and politicians alongside the fabulous photograph cabinet of late Victorian performers, or indeed the selection of images from Suffragette marches. However, the sentiment often falls a bit flat: it’s all well and good having a corner dedicated to Tudor women in power, but it loses its impact when the contemporary collection still contains paintings by Allen Jones (alongside the obligatory “well, some people find his furniture a bit icky” addition on the placard) or photographs of Tracey Emin naked and on all fours (I notice, also, that there appeared to be only one naked portrait of men compared to the dozens of nude women on display). I was admittedly relieved to hear that the gallery has no interest in playing the cancellation game (gallery director Nicholas Cullinan told The Telegraph that they were “not here to make moral judgements about people [...] most [people] understand that everyone does good and bad things.”). However, there’s still something slightly nefarious about using the overly-academicised, leftist visual (and literal) language of revisionist curation while refusing to update the collection accordingly.

One of the few male nudes at the National Portrait Gallery | Gilbert & George, In the Piss, 1997

The National Portrait Gallery's re-opening sheds light on an obvious yet easily forgotten truth of museum curation: no amount of avant-garde architecture or progressive placards can save a collection if the artwork itself is bad. It's reassuring that the quality is low throughout the entire institution as opposed to just one type or period of portraiture, suggesting overall a mere lack of taste rather than of knowledge. This is not a problem exclusive to portrait galleries, but it is more common among them: curators are often prone to let the the character of the sitter overshadow the quality of the work. Yet it's still disappointing that after three years, millions of pounds, and an acquisitional increase of a third that the new works aren't good enough to lift up the rest, or indeed that British painters and photographers don't appear to be producing particularly high caliber work. It's likely that this isn't the case, and that the big brasses just aren't particularly brushed up on their basic art history (or, more likely, are only willing to dole out the cash to very specific friends and institutions). However, the consequences of bad curation in public museums are more concerning than mere snobbishness: if the British public is not exposed to good art, how will they know how to recognise it, or indeed, make it?

Cover image: Anna Wintour, Alex Katz, 2009