WICCAN, ARTIST & QUEER ACTIVIST: INSIDE THE SUBVERSIVE WORLD OF OLIVIA STRANGE

- Raegan Rubin

- Mar 4, 2024

- 5 min read

"To me, that's the apogee of what art is about; making the unspeakable speakable and making the unknowable knowable with liberal fluidity and empathy."

Image courtesy of The London Art Fair.

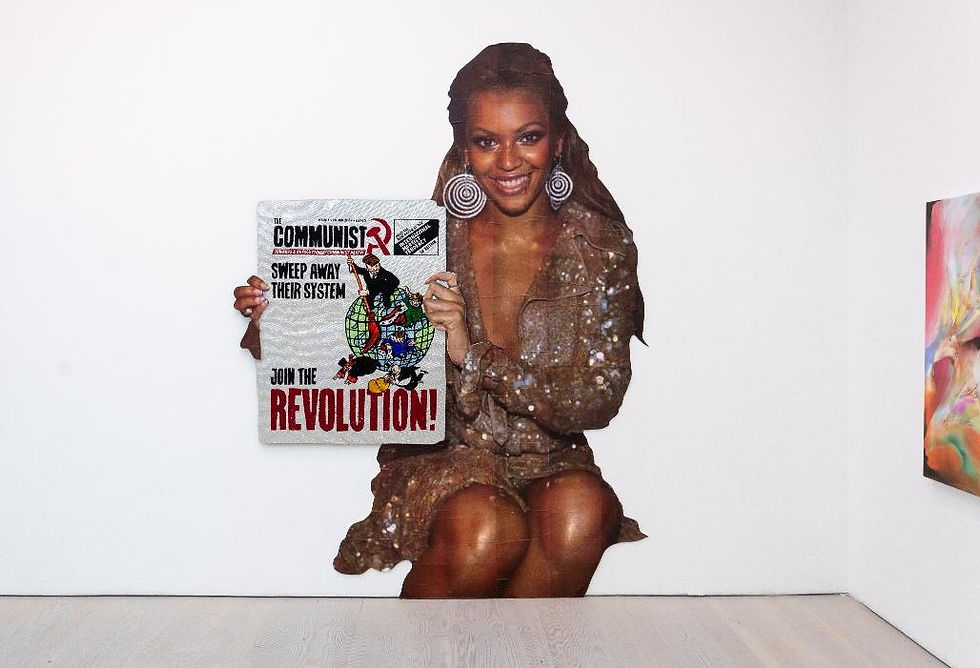

Since she was a child, the queer multimedia artist Olivia Strange was inexorably drawn to daydreaming and painting. "I needed another space to exist in and be imaginative," she says in an exclusive interview following her exhibition at the Liminal Art Gallery stand in the Platform section of London Art Fair curated by Gemma Rolls-Bentley. A highlight of the fair London Art Fair, its evening debut invited visitors to connect with a series of visceral sculptures. For Strange, objects symbolise "portals to other places and spaces in time. They enable me to play out ideas, fantasies or identities that typically don't feel safe to do in the everyday reality."

Strange & Carr at The London Art Fair 2024.

The event was marked by a healing ritual led by fellow witch and Wiccan High Priestess Tree Carr. A long-time friend, Carr has done Tarot readings for Strange and the artist regularly attends her moon circle twice a month. Together, they offered guests the opportunity to call forth the four elements and cast a circle that "sent healing to all human and sentient life currently being oppressed on the planet."

The ceremony was a welcome release from the raw emotions evoked by the exhibition. Malevolent claw-like nails cast in plaster, a singular clutched breast, fingers welded together with nails and a hand groping the right buttock, its display was a stark assault on the human body. With each sculpted gesture, Strange challenged her audience to deconstruct patriarchal ideas of identity, female desire and shame surrounding power-play. "There is an element of voyeurism in my work,” says Strange. “I'm confronting the viewer with objectified ligaments that are dislocated from the body and attached to the wall. In the same way that you would look at a garment in a shop."

The artist's works are inherently iconoclastic; often discussing gender politics with sexual and mythological motifs that have a sinister edge. "I try to reclaim stereotypes with symbolic objects like the carabiner clip- a meaningful object within queer culture," says Strange. Similarly, Vendetta di Persephone (2021) is a piece featuring a pomegranate in reference to the Greek myth of Persephone and Hades, as well as the alleged forbidden fruit eaten by the first woman Eve. Both figures are seen by Strange as victims of patriarchal stories of persecution and "demonised for being sexual beings.' By retelling their stories through her work, she hopes to "reclaim their power," and offer an alternative intersectional queer feminist narrative.

Olivia Strange, Vendetta di Persephone, 2021. Image courtesy of artist.

Perhaps what's most striking is Strange's use of hard and soft mediums to create tension, restore sexual agency and subvert female desire. Combining fragile candy floss pink and abrasive "Pepto Bismol pink" with romanesque pillars, metal spikes, snakes, clam and oyster shells, and vulvic forms dripping with bodily fluids, the artist celebrates the eroticised state while recontextualizing it as an impenetrable, dynamic force. "The Delicious Things They're Doing (2022) speaks to voyeurism and unconventional ways of experiencing pleasure," says Strange about the piece depicting a hand pointing a razor-sharp fingernail at a clutched breast. While

disconcerting, its somewhat grotesque nature can also be interpreted as a harsh critique on the male gaze, and its tendency to demean female desire as monstrous. Take into account the artist's queer lens and another universal layer of meaning emerges. "It allows dualities and complexities to exist beside each other, without categorising them," says Strange. "It suggests fluidity and a rejection of normative ideals, which is ultimately what queerness is all about."

As a testament of her inclusivity, the artist is careful to welcome all denominations of the LGBTQIA+ community by spelling 'women' as 'womxn' throughout her digital and printed copy. "I don't want my work to be pigeon-holed as only about the historical persecution of women," says Strange. "It's intended to speak to the injustice of all groups of people who are punished unnecessarily simply for being who they are." The creative's self-awareness regarding her own sexuality grew in tandem with her artistic practice, and her queerness became all the more prescient when she was studying her Masters. "While I became increasingly aware of my queerness, I didn't have the confidence to do anything about it because it was wrapped up in ideas of (un)worthiness and taking up space." Naturally, Strange turned to her Dracaena Marginata plant (called Dracaena) to be a catalyst for her exploration. Similar to how she lovingly interacts with objects today, the creative wrote "intensely poetic-emo love letters'' to the plant, and soon created a large-scale multimedia installation that manifested a “liminal and magical” dreamscape.

Draceana you take me to tropi-ca-na-na, 2016. Installation view courtesy of artist.

"Dracaena. You take me away and I love you for that. Sweet smell blue. Stowaway silia. Yellow lello your white light is blissfully blinding. On the brow of utopia salty sweat drips and I am succumbed. Dracaena don’t leave me.”

-- Excerpt from ‘Love Letters to Dracaena’( 2016).

Strange's reverence for nature and her desire for the universal acceptance of socially misjudged communities, brings us full circle to the healing ceremony she conducted with Carr at the Liminal Gallery. Today, witchcraft is synonymous with ideas of self-realisation, setting intentions and living in harmony with nature and one another. Strange's sculptures embrace all of the above and then some; engaging with the tragic history of mediaeval witch trials and the religious crusade against sexual deviance and female authority, or anyone deemed to be living outside of the social norm. Malleus Male-f*ck-u-rum (2022) for instance, is a two-piece sculpture alluding to the 1486 treatise Malleus Maleficarum (Hammer of Witches). The fifteenth-century tome was a guide for hunting and persecuting witches that would heavily influence the next 200 years of the European witch craze. In response, Strange's piece features a static foot and unfurling fist topped with leaves and oyster shells; reminding viewers of the book's insidious legacy.

Olivia Strange, Malleus Male-f*ck-u-rum, 2022. Image courtesy of the artist.

"It's a direct rejection of how the book labelled autonomous, powerful women as evil," says Strange. "Female self-pleasure was demonised and women were sexualized as having an insatiable, carnal lust that would lead them to greet the devil through lesbian and straight sexual acts. It suggested that to survive, one must be a ‘good girl;’ essentially becoming submissive to the standards set by the patriarchy. It just makes me really angry, especially as we are currently seeing history repeating itself with transphobic rhetoric from political leaders and people in power." Suitably, the work exudes with palpable aggravation from its blood-red nails and protruding spike down to the rigid posturing and belt fastened around the heel.

Strange is set to return to Liminal Gallery in August for her physical solo show. The artist also hints that the future may see her express herself with her formative medium of painting, and we can’t wait to see what she has next in store.

On January 20th, Strange participated in a panel talk that delved further into the themes discussed in this article. Alongside fellow contemporary queer artists Shadi Al-Atallah and Zach Toppin, she spoke to Platform guest curator Gemma Rolls-Bentley about how her work reflects the resilience, the beauty and the passion of queer love and life. The panel recording is available to listen toe here.

Raegan Rubin is London-based freelance journalist specialised in art and fashion history, subcultures, social justice, sustainability, LGBTQ+ and Fetish culture.