ELLEANA CHAPMAN & COMRADE BEYONCÉ

- Ruby Mitchell

- 17 minutes ago

- 3 min read

Can celebrity and communist praxis co-exist, or is specious to to use fame as a function of class struggle? Ruby Mitchell takes a look the rhinestoned agitprop of Elleana Chapman at Good Eye Project's group show at the Saatchi.

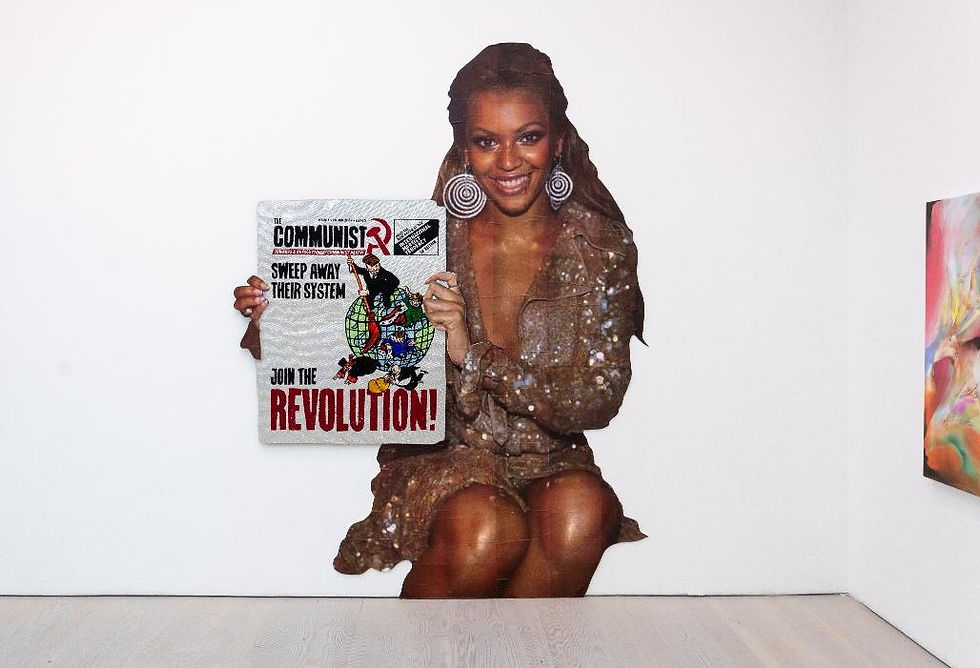

Elleana Chapman, Comrade Beyonce, 2025

There’s a persistent lie in contemporary art that political commitment should be visually restrained, morally severe, and suspicious of pleasure. Elleana Chapman’s practice exists in direct opposition to this, espeically and fitting that her work appears here as part of Good Eye Projects’ annual return to Saatchi Gallery, a group exhibition bringing together artists from the residency programme’s Autumn 2024, Spring 2025, and Summer 2025 cohorts.

In her latest body of work, Chapman hurtles herself into the realm of spectacular agitprop. Attack of the 50 Foot Comrade (2025), a towering composition made from rhinestones, glue, acrylic, plywood, inkjet prints and wheatpaste, unifies the unfathomably grand scale of mass propaganda with the material language of pop culture. This colossal collage-installation, shown at the Saatchi Gallery with Good Eye Projects, brings revolutionary imagery into the register of everyday spectacle: Lenin becomes companion to a fabulously reimagined Beyoncé, and communist slogans are rendered as billboard-scale calls to action – “JOIN THE REVOLUTION!” Chapman investigates the political potential of art to catalyse class struggle, but critically, she does so without an aesthetic of self-flagellation. Rhinestones, kittens, glitter-glue, pop divas - all the material language of class, taste, and mass culture – she mobilises these deliberately. Often, ‘low’ aesthetics are only tolerated when sanitised - made ironic or anthropologically curious.

Elleana Chapman, Comrade Chapman, 2025 (details)

Chapman’s work exists out of this safety net. Her rhinestones are excessive because excess itself is the whole point! They are an affront to bourgeois restraint, and to the serious, chin-stroking, bowed-head reverence reserved for high art and its institutions. There is something fantastic in Chapman’s embrace of excess (she proudly embodies Chavvy Chic™). She refuses class shame and, in doing so, exposes much of the classism that underwrites so much of contemporary aesthetic judgment.

Chapman is an artist whose political organisation is itself a social practice. A member of Revolutionary Communist International, her ideology is a lived infrastructure that informs how she thinks about image and audience. Her studio practice - a speculative agitprop lab - asks us what political communication might look like if we were to stop fetishising political sanctity and start reckoning seriously with how people actually encounter ideas.

Comrades Lenin, Beyoncé and Trotsky discuss the Party, 2025

Celebrity as structure (rather than endorsement) is a prevalent theme for Chapman. She has an ongoing engagement with figures like Beyoncé, Kylie Minogue, and Britney Spears – all of whom act as an organising apparatus for identification. Her bedazzled Comrades Lenin, Beyonce and Trotsky has an instructive quality: just as a newspaper can act as the organisational framework for the revolutionary party, celebrity operates today as a ready-made infrastructure through which ideas are circulated and contested. Chapman’s staged encounters ask us what happens when the mass character of pop stardom is forced to reckon with class struggle.

Run the World (Proles) (2025)

Take, for example, Run the World (Proles) (2025), where Beyonce’s feminist anthem is recontextualised as a call for class solidarity, playing from a hot-pink iPod atop a wheatpasted newspaper clipping. Chapman does not cancel Beyoncé’s cultural influence but instead examines its limits. Beyoncé may have done remarkable work in foregrounding Black culture and gender politics within the mainstream, but a line has been drawn by political economy. Without confronting capitalism, you can’t meaningfully dismantle racism or sexism, for they exist in the capitalist system that requires and reproduces them.

Her imagined “Comrade Beyoncé” is a proposition: what if the immense affective power of celebrity were redirected toward collective struggle as opposed to individual empowerment? Could fandom be politicised as organisation>consumption? These speculative exercises in political imagination are fun – they’re rendered in glitter and glue. Escapist play is the visual language of the terrain Chapman is working on – which is what makes her work so engaging. Her practice is sincere, didactic, and unafraid of persuasion.

Installation photography courtesy of Saatchi Gallery

If I take anything from Chapman’s work, its that pleasure is not the enemy of sincerity. She stages communism through the fabulous and the familiar, clarifying its demands. Revolution does not need to be ascetic: it can be experienced in the images, sounds and desires that already structure our lives. If Chapman’s revolution feels unfamiliar, maybe that’s because we’ve been trained to distrust anything that looks like fun.

Elleana Chapman is exhibiting at the Saatchi Gallery with Good Eye Projects from 29 January – 1 March 2026.