“FOR NO ONE IS FREE UNTIL WE ARE ALL FREE”: ‘UNRAVEL: THE POWERS AND POLITICS OF TEXTILES IN ART’ AT THE BARBICAN

- Daisy Culleton

- May 27, 2024

- 3 min read

From large-scale sculptures to intimate embroideries, woven both metaphorically and physically into every piece of the Barbican's Unravel: The Powers and Politics of Textiles in Art is the distinct tale of an artist’s marginalisation. Socio-political narratives relating to issues of displacement, violence, ancestry, gender and sexuality unfold. Each fibre, thread and yarn embodies the artist’s endeavour to deconstruct authority and reclaim their power. writes Daisy Culleton.

Solange Pessoa, Hammock (part of 4 Hammocks), 1999-2003, photography courtesy of Chi Lam

Ninety-four commanding artworks by forty-four international practitioners, nine politically charged blank spaces and one powerful letter pinned to the wall: this is what occupies the Barbican's third-level gallery space as part of its exhibition Unravel: The Powers and Politics of Textiles in Art.

Textiles, as a medium, have faced significant injustices throughout Western art history. Scholars have consistently relegated the fine art practice to the rank of craft, labelling it as a purely "feminine" practice - and therefore unworthy of consideration - due to its outwardly domestic usage. Co-curated by the Barbican (London) and the Stedelijk Museum (Amsterdam), Unravel offers a multi-generational insight into how artists have taken the historically inferior medium and transformed it into a vehicle of empowerment. Finding comfort in their shared experience with the medium, the artists on display use it as a mode of resistance and transgression against hierarchical power structures.

From left to right: Tracey Emin, No Chance (What a Year), 1999, Feliciano Centurión, Eye with ñandutí, 1994

In No Chance (WHAT A YEAR) (1999) Tracey Emin recounts the inner turmoil and longing that she experienced in 1977, the year a man raped her. The hand-stitched appliqué blanket embellished with bold confrontational text cut out in felt tells a loud and unavoidable story of a girl who felt silenced; ‘at the age of 13 why the hell should I trust anyone’. Feliciano Centurión’s Eye with ñandutí (1994) demands attention: produced following his HIV diagnosis, the large singular eye painted in the centre of the ñandutí (a traditional Paraguayan lacework) evokes a concoction of art, spirituality and cultural heritage to process trauma.

Mrinalini Mukherjee, Vanshri, 1994, Sri, 1982, Pakshi, 1985

The figures of Mrinalini Mukherjee’s macrame sculptures, Vanshri (1994), Sri (1982) and Pakshi (1985) require no introduction. The anthropomorphic deities, powerful figures of sacred female sexuality, have an awe-inspiring presence that can be felt at every corner of the exhibition. Stylistically informed by her Indian heritage, the abstract three-dimensional effigies push the boundaries of what it means to be a textile artist.

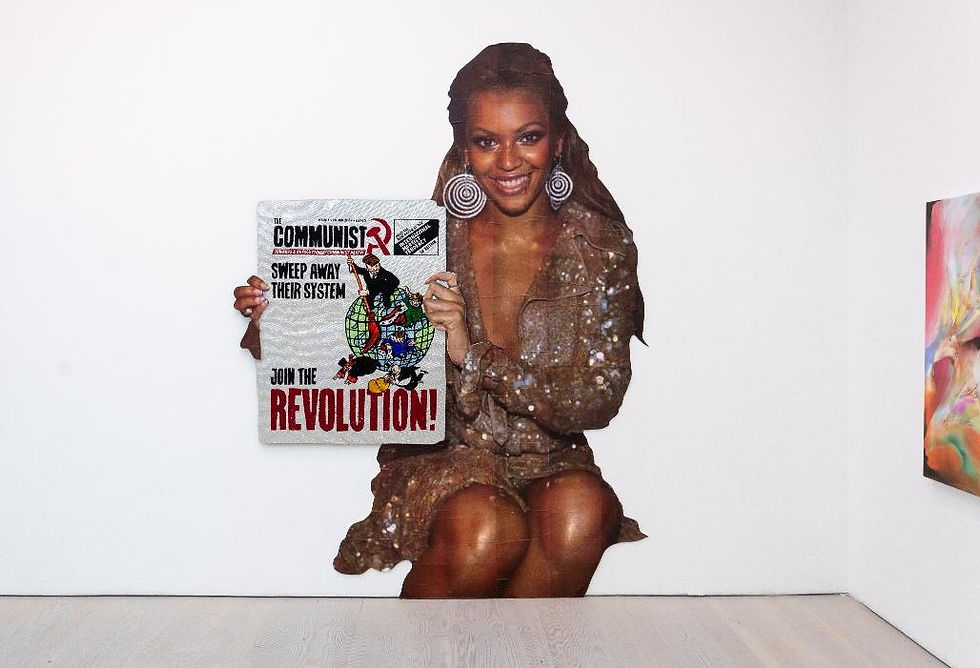

Installation views courtesy of Jo Underhill and Jemima Yong / Barbican Art Gallery

Despite this undeniably stimulating mix of artworks, it is the nine blank spaces dotted about that consume most of my thoughts about the exhibition. On February 14th the Barbican published a statement regarding their decision not to host the London Review of Books (LRB) Winter Lecture Series, wherein they stated that the choice has been finalised following concerns surrounding Pankaj Mishra’s lecture The Shoah after Gaza, in which Mishra accused Israel of participating in the same genocidal practices committed against the Jewish population at the start of the twentieth century. This action induced censorship accusations that prompted six artists to withdraw nine of their works in solidarity with Gaza.

Mounira al Solh, Letter to the Barbican, photography courtesy of Daisy Culleton

Mounira al Solh’s powerfully countered the absence of her work with her resonant voice, which she articulated through a letter laced with a potent message left in its space. Addressed to the Barbican administrative team, Solh wrote, ‘What would my artwork do, when shown lonely in an art institution whereby speakers who are raising their voices for justice are being cancelled? For no one is free, until we are all free, as Martin Luther King famously said.”

Solh’s words and the accompanying blank spaces pay testament to the thematic concerns of the exhibition in a way that could not have been foreseen. Unravel: The Powers and Politics of Textiles in Art at the Barbican thus invites spectators to question the issue of power in a very real sense and calls into question how art institutions continue to display and interact with oppression.

Unravel: The Powers and Politics of Textiles in Art was shown at the Barbican from 13th February to March 26th, 2024. It is set to move to the Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam in September 2024.

Daisy Culleton is an Essex-based writer with a degree in BA American Studies and History from the University of Nottingham. She writes about sustainable fashion in her Substack publication VNTG.