WE'RE ALL HOME ON ME'S BABYDOLLS

- Ruby Mitchell

- Jun 10, 2025

- 4 min read

Updated: Jun 11, 2025

“We don’t perceive beauty as a linear concept,” say Sahara Hirani Harji and Zehra Marikar, the duo behind Home on Me Collective. Their latest exhibition Babydoll at Indra Gallery is their most ambitious yet, foregrounding the aesthetic tensions between the saccharine and the sinister, and unsettling distinctions between pleasure and discomfort. Babydoll is “a cute pet name, or a title that could creep someone out,” they explain, drawing on the resurgence of the trending Lolita aesthetic and its subversions.

Since its founding, Home on Me has grown into a curatorial platform that resists posturing and institutional gatekeeping. “We don’t feel above our artists, we feel like peers,” they said. “Art provides a lot of joy and substance, and it doesn’t need to be confusing. The main way we are reshaping collector-artist relationships is making it far less complex.” Their model of curation is decolonial not through didacticism, but through tone, accessibility, and trust. They tend to veer away from White Cube minimalist practices and “love to have some themes that embrace maximalism or what has historically been seen as ‘lower’ culture, or ‘tacky’.”

Photography courtesy of Home on Me Collective

The works across the show - crawling with body horror, kitsch, camp and queered desire - draw on a Deleuzean and Guattarian sense of the minor: aesthetics that resist dominant narratives and refuse resolution - centering the fragmentary and the subversive. Discomfort seems inherent to many, particularly in an age shaped by resurgent far-right conservatism and the reassertion of patriarchal values - where femininity, queerness, and bodily autonomy are not just interrogated but actively legislated against, aestheticised, commodified, or rendered suspect. If discomfort is often disavowed in the increasingly precarious arts economy (where legibility, brand coherence, and palatability are informally demanded), Babydoll wagers the opposite. That disturbance can be generative, not only as a psychic or somatic state but as a curatorial grammar. The show foregrounds the abject, the unresolved, the grotesque and the too-cute as modes of political resistance. In a cultural moment that asks women and marginalised artists to either soothe discomfort or sanitise it, Babydoll instead lets it sit, squirm, and leak. If Babydoll unsettles, maybe it’s because it reminds us that softness is always on the verge of rot.

This logic - discomfort as form, rot as method, cuteness as camouflage - recurs across the exhibited works. Each artist engages the unstable boundaries of identity, desire, and embodiment through formal strategies that resist closure.

From left to right: Vikalp Durga Mishra, Haanthi Mattha & Chinmayananda

Vikalp Durga Mishra

Vikalp Durga Mishra’s figures look back at you with big eyes that are “not angry or sad, just there” - a gaze that quietly refuses pathos. “I never had those set of eyes growing up,” he says, describing them as “a neutral human point of view… eyes to look at with empathy.” Haanthi Mattha (which translates to “Elephant Forehead”) explores this, Mishra confronting the rigid beauty ideals of his upbringing - where, as he says, his culture “hold[s] beauty to a very conventional standard.” For Mishra, exhibiting in Babydoll with Home on Me Collective feels “surreal” - likened to a fated kinship. “It feels like [being] one with the consciousness,” he says, “one with people who think alike… my people who I was destined to meet.” There’s an emotional clarity in his voice: Babydoll a convergence of sensibilities and of shared strangeness.

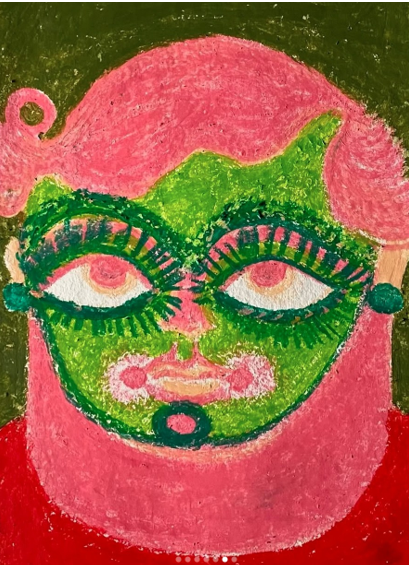

“I really enjoy observing people,” he explains. He found inspiration for his oil portraits at the gymnasium. He describes a scene of theatrical flair. “Straight men peacocking… drenched in sweat… pushing their chests out, rib cages popping. I could feel them bursting into something.” That tension - between containment and exposure - bleeds into the oil stick, where faces dissolve into thick strokes of green, pink and red. “They’re removing layers in front of me,” Mishra says. “They want to peel their skin off and show themselves.”

From left to right: Chrysa Kanari, The Woman I & The Woman

Chrysa Kanari

Chrysa Kanari’s portraits operate within the psychic terrain Kristeva names the abject - what is expelled but does not disappear. The faces she paints are flattened, flesh-toned and mask-like: too close and uncanny. Slack-mouthed and spatially suspended, they resist classification as either living or inert. The refusal of expression, context, and spatial grounding pushes them into a liminal state, disturbing in any passivity. Kanari adopts the horror trope and pares it back to something forensic. Her oeuvre explores “the rotten and criminal aspect of the human condition; illness, crime, war, atrocity, as manifested in the forsaken body”. She documents the body as a ‘remainder’: unclaimed, unclean, and ungrievable.

Estelle Simpson

Estelle Simpson’s paintings stage what she calls a merging of “the quotidian and balletic notes,” where the domestic and theatrical collapse into surreal, often uncanny tableaux. Her practice draws directly from a past in ballet, not only in subject matter - mirrors, curtains, swans - but in the choreography of mark-making itself. “My works are meditations on how my formative years of ballet education have an impact on my everyday experience,” she explains, particularly the “dramatic gestures of the stage” as they filter into private life. Ballet’s aesthetic legacy - its obsession with form - is reimagined through a feminist lens that refuses idealisation. “I wish to respectfully create ambiences that are filled with wonder and awe,” she writes, “but still are sensitive as to not over-romanticise the experiences of being a woman both in the world of dance and in everyday life.” The mirror, once a tool of discipline, reappears in her work as an ambivalent symbol - used to “magnify certain details” like a cat’s fur or a swan’s feathers, but also to “unpick a traumatic relationship” with surveillance, repetition, and the performance of beauty.

Nele Mark

Nele Mark’s Mahlstrom drawings speak to an unstable terrain, one anchored less in narrative than in sensation. “Drawing is a way of being present for me,” she says, describing the act as a form of exposure, “revealing a layer of reality that feels uncanny and hard to fully grasp.” Installed back-to-back, the works invite a slow circling, echoing the “whirl” of the title and drawing viewers into a fugue of overstimulated estrangement. “My thoughts often circle around the experience of intense emotions in today’s hectic society, and the feeling of loneliness that can come with it.” For Mark, Babydoll’s curatorial cohesion amplified this: “I loved the way the artworks connected with one another … together creating a surreal, dream-like realm.”