“I AM THE SUBJECT OF MY WORK, NOT SOMEONE ELSE’S OBJECT”: PENNY SLINGER’S 'EXORCISM: INSIDE OUT' AT RICHARD SALTOUN

- Avantika Pathania

- Aug 21, 2024

- 10 min read

Updated: Sep 17, 2024

Exorcism: Inside Out, by Feminist Surrealist Penny Slinger (b. 1947) at Richard Saltoun features Slinger’s original photo-collages, prints, and video works, coinciding with the release of her notable book, ‘An Exorcism: A Photo Romance’ by Fulgur Press on June 21, 2024. The exhibition is regarded as one of the most ambitious undertakings at Richard Saltoun and presents Slinger’s artistic evolution as she merges her body with archetypal landscapes, addressing themes of fetishism and sexploitation from a feminist perspective. This autobiographical journey is vividly depicted within the Gothic confines of Lilford Hall, fusing the nostalgic beauty of British neo-Romantic painting with the spectral bewitchment of horror cinema.

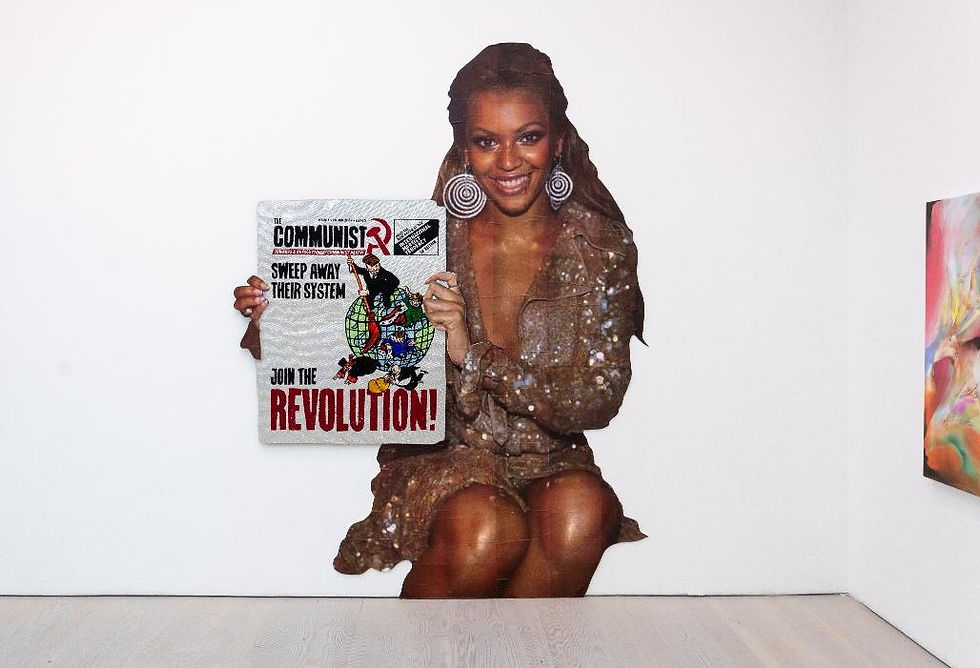

Installation photography courtesy of Avantika Pathania

Avantika Pathania: Your work often involves deeply personal themes with broader feminist discourse. What personal experiences influenced the creation of this exhibition and how do they reflect in your art?

Penny Slinger: This was a very specifically geared project that went over seven years, believe it or not. It was triggered by my feelings; I was feeling like I was breaking down. I lost my very important significant other, who was Peter Whitehead, the filmmaker. I was part of this first all-Woman’s Theatre group, run by Jane Arden. We performed A New Communion for Freaks, Prophets, and Witches at the Open Space in London, and then went on to make a film called The Other Side of the Underneath [in 1972]. In the process of making this film, things happened that ended up breaking up our relationship. After that, I felt quite devastated. It felt like my male energy, and my female energy, had all kind of just left me in tatters. I felt broken, and did not know who I was anymore. So, I embarked on this journey, really, of self-discovery, and of trying to find out, who am I, what are these feelings that I have? How do I get to grips with it, and I thought, the best way to get to grips with it was to try and really uncover all those darker areas, look at the skeletons in the cupboard, my fantasies, all the things that we usually keep hidden away, and use this house, this wonderful mansion that we found as a setting, to go into all the rooms and see tumours being a facet of myself that I was trying to understand, and to understand what my society had delivered to me as a person, what my relationship projections were, and to try and separate myself, and who am I in essence out of all this.

Stills from The Other Side of Underneath, dir. Jane Arden

In that process, it was a very deep plunge, and it was really a death and rebirth experience. I think you can have a parallel to the hero’s journey. But this one’s the heroine’s journey, we don’t have many heroines. I wanted a map and show it and expose it. It is called An Exorcism, because I wanted to exorcise myself from all the things that were holding me back, all the fears or the traumas, and then try and get myself to be able to come reborn out of all of this, and take my own life in my own hands. I felt that if I could do it for myself, and put-up signposts along the way, that it would be incredibly useful to other people, because we all have our own dark nights of the soul. And we feel like we are alone and that nobody else feels that way. So, I thought if I expose all the underbelly, all those sensitive places, and bring them to the light of day and show them and show that I made it through to the other end, that this would be incredibly helpful. I also took personal experiences, but tried to render them in an archetypal form, so that it could resonate with other people, not in the specifics, but in the archetypes and in the myth that I was weaving.

Your exhibition transforms the gallery into an immersive audio-visual environment. Can you describe the process?

Right from when I was a young artist, I wanted to do things that were more of an experience than just having art on the walls, people to be just immersed, literally, in the art in a way that was visceral. It’s not just a question of showing people my work, I want to give people experiences and it’s really taken all this time before I’ve been able to do something on my terms. And thanks to Richard Saltoun, who saw what I did with Dior, and he said, “why don’t we do something like that for Exorcism?” And I said “Oh, thank you. You’re speaking my language!”

Your collaboration with Dior in 2019 significantly influenced Exorcism: Inside Out. How did this haute couture project shape the current exhibition?

[The reason] Maria Garzia wanted to work with me was because she was familiar with my work. She loved that work [An Exorcism series] and she wanted me to do something along those lines with Avenue Montaigne, because it was going to be the last time they would be able to have an actual couture show there. They are moving their creative studio, and wanted some powerful transformation. So, I literally as I did here, turned the inside out and the only outside in. and had all the elements placed all over. And then came out at the end with this pure gold dollhouse rendition of the facade of the building. That was the alchemy. And that was the process: going through the elements and renewing and coming out and taking that gold, the essence of it. Of course, we had a grand budget for that. But we felt that we could do something that would create an environment, a space, a journey for people to come into rather than just art on the walls.

Your work has been described as creating a new language for the feminine psyche. Can you elaborate on what this language entails and how it manifests in your art?

When I was a student, I was looking to see what do I want to do for my thesis? I knew I was interested in the human form, and particularly the feminine. I’m a woman, it seems to be the lens through which I experience reality. So, I thought that was very relevant, coupled with the fact that I saw throughout the history of art, the feminine form, and especially the nude feminine was key and central all the way through, but generally seen through the lens of a male artist. I wanted to take that back and be my own muse, and to create a language that was showing not just how I look or how a woman looks, but how she feels inside, what her fantasy life is, what are her dreams and imaginations, and all that that goes on beneath the surface. So, when I discovered the work of Max Ernst, I saw a wonderful language, and how surrealism was used to be able to depict the psyche, to be able to show those hidden grounds. But I had not seen it used yet to describe the feminine psyche. So, that’s what I chose and decided “I want to do this.” My first book was all about showing that other 50 percent of women that we don’t usually see.

From left to right: Penny Slinger, A Difficult Position 2, 1970-1977, Hang Up, 1970-77

As you said, feminist surrealism is also a core element of your artistic identity. How do you see this movement evolving? And what do you envision your work playing in its future?

I see that a lot of young women are really using this kind of language, and they’re using their own bodies in the way that I chose to do that I didn’t see done very much before, which is being able to say "I am the subject of my work, I am not someone else’s object, I am a subject. And I’m going to choose how I display myself. If I’m naked, it is because I’m choosing to show that because I’m proud, not ashamed. I want to be present in my full glory". Therefore, in that intention, I’ve seen a lot of younger artists using their bodies using themselves in this great, surreal way. Because it is so much easier, I think, to chop up and slice and dice yourself, that taking somebody else and taking those liberties with them. I felt like using myself, I could take whatever liberties I like. And I see a lot of young women taking several liberties now and I really enjoy it.

This exhibition features a never-before-seen video (An Exorcism - The Works (2019)) related to Exorcism: Inside Out. What can the visitors expect from this video? How does it complement to the rest of your exhibition?

We made the video in 2019, myself and my partner, Dhiren. I was very lucky that I had all the negatives of the empty rooms and grounds so I was able to digitize those, print those out. Then I disassembled, deconstructed all my collages, and then put them together again, in this animation. So, we’re literally going into the worlds of the collages, and the elements stand in space in relation to each other. It is a very simple formula, in that it is only the collages, I haven’t used any other material. It’s just my voice saying the titles and then a little bit at the end where I’m kind of summing it all up just as a spontaneous transmission. The music was created specially to create the moods for each of the pieces, and it’s completely the same sequence and images that are in the new edition of An Exorcism. They complement each other either way perfectly. I added this element as an extra space. I created the film because I was showing a lot of the collages, they were maybe a handful of collages, but with no context. So, I wanted to let people know, this is the context of all this work, and this is the whole journey. Then you can see the pieces in relation to what that whole journey is. So, the film represented that way of allowing people to feel it all, when there was just a scattering of artworks.

From left to right: Penny Slinger, Self Image, 1970-77, He Crows, He Crows, He Crows, 1969

How do you decide which medium to use for a particular project, how do they interact with your current exhibition?

I’ve always loved to work in many media, kind of simultaneously. When I was a student, I was a complete pain in the arse for everybody, because I wanted to mix photography with painting and sculpture with everything. At that point (I know it’s much more of a trend now), it wasn’t as much. I wanted to shake it all up together, and come up with new associations, new formulas. I was going to go to the Royal College Film School, and I met Peter Whitehead, and worked with him instead to make films. I thought film was a very nice kind of catch all for different art forms. You could put all these different media, making a costume, creating an environment, painting, all those things can go into a film. And then, you have this extra element of time. And I’ve always rather loved the idea of, instead of linear time, a kind of timeless space that you create with that medium. I do have a bunch of media, at my fingertips to use for any specific project, and each of them have their own discipline. I guess I just intuit, and depending on what my capabilities are, I choose to work in a particular medium. But I would say collage is my focus, and that has been true for the different media, different forms of collage.

There is a recurring theme of roses, especially the rose scent lingering in the exhibition space. Can you tell us more about it?

I think the rose garden has been one of those archetypal glyphs that I’ve resonated with. Since a child, I always used to love the idea of the ‘secret garden,’ of a walled enclosure as private, and somehow seeming to be a place set apart, apart from all over the world, and mystical and sensual and all those flavours. I wanted to evoke that sentiment so often. The rose garden has appeared in many different forms in many of my different projects. And there's a whole chapter in An Exorcism, called the ‘Rose Garden.’ I’m using it as a symbol for a woman, finding her burgeoning sensuality, and accepting that and kind of just tuning in with nature and the natural world that was so cut off from but seeing that her sensuality as being a part of the sensuality of nature.

From left to right: Penny Slinger, A Rose By Any Other Name, 1969, Memory, 1969. Photography courtesy of gallery.

An Exorcism was originally deemed too controversial to be published in the UK due to its explicit content, how do you feel about it being released eventually?

Well, the first version of the book came out in 1977, with a grant from Roland Penrose, his Elephant Trust, and that was just 99 images with the titles. Then I wrote at the same time, this other version, and it was going to come out a couple of years later with another publisher, Dragon’s Dream. However, they also chose to publish another book of mine, Mountain Ecstasy. [That] was the one that got seized by British customs coming in to England from Holland where it was printed, and they burned thousands of copies. When that happened, the publisher decided not to do An Exorcism after all, so I got everything back from them. And then I sat on it all these years, until now, Robert Shehu-Ansell of Fulger Press, decided “we should do it.” I’m delighted, both doing an immersive exhibition like this, and bringing a book out that I had ready to go so long ago, waiting all this time to come out. But then I guess my name is Penelope! So, patience, whether I like it or not. I do feel that everything is timeless. It’s not just fixed in a particular place and time and that if it’s archetypal enough, it will not have a shelf life. Whether it came up then or now it’s actually fate. And here we are. I am so grateful to be able to present it now.

Exorcism: Inside Out by Penny Slinger runs from 3 July – 7 September at Richard Saltoun, 41 Dover Street, London.

Avantika Pathania is a London-based writer and arts journalist.