THE METAMODERNISM OF KAARI UPSON

- Arina Baburskova

- Oct 29, 2025

- 4 min read

“The parody just never fully cancels out the ache.”

In her reading of Kaari Upson's House to Body Shift at Sprüth Magers, Arina Baburskova reframes the late artist's work as a study in metamodern oscillation and the restless movement “back and forth between irony and sincerity, critique and care.”

Exhibition shot courtesy of Sprüth Magers

Flesh-toned furniture slumps scattered under Sprüce Magers's cold light, sharp and clinical, as if under inspection. Staircases curl in latex; chandeliers sag like exhausted limbs; fences warp into forms that are half-body, half-architecture. They feel less like furniture than specimens, or uncanny organs sculpted into domestic shapes. In silicone and latex, as well as charcoal, paper, and video, the body and its traces dissolve into these pieces, only to reappear again as fragments - unsettling, yet sincere. From her earliest works in The Larry Project to later series drawn from her childhood home in California, the late American artist Kaari Upson (1970 - 2021) explored the intimate, often uneasy connections between people and the spaces they inhabit.

Exhibition shot courtesy of Sprüth Magers.

Through the floor-to-ceiling glass of the gallery space, her haunting, dollhouse-like interiors are glimpsed from the street, a counterpoint to Mayfair’s polished façades. As if echoing Maison Estelle’s (the next-door neighbour) promised comfort and luxury beyond its guarded doors, for its latest show, Sprüth Magers invites you into the uncanny domesticity that is turned inside out once you enter. Yet this tension feels fitting for a gallery rooted in Cologne and now spread across Berlin, Los Angeles, New York, and London, long known for exhibiting the likes of Cindy Sherman, Barbara Kruger, and Anne Imhof, and championing artists who fracture image, identity, and reality.

Similarly, Kaari Upson (1970–2021) first came to prominence via the Larry Project (2003–2011), a sprawling body of work that began with an abandoned trove of personal belongings from her neighbour’s burned-down home in San Bernardino. Letters, photographs, journals, clothing - fragments of a man called 'Larry', a self-styled Playboy figure dabbling in self-help therapies, fantasy, and excess - became both her material and her muse. From this debris, Upson built not only a portrait, but a wider allegory of American suburbia: aspiration, obsession, loneliness, and projection refracted through her own imagined role as the ‘blonde girl next door’ via an inverted Virgin Suicides scenario, where instead of adolescent boys constructing mythologies around distant girls, Upson mythologised the man across the street.

The resulting works blurred candidness and parody. In them, the body folds into the home, and the home back into the body, again and again, until both dissolve into uncanny doubles. Larry’s ghost lingers not as an individual, but as an idea.

Though most of the Larry works were made over twenty years ago, gathered here alongside Upson’s later pieces, they feel less like postmodern pastiche than an early sketch of the metamodern condition. The sincerity of her suburban excavation sits almost uncomfortably close to its absurdity; the parody just never fully cancels out the ache.

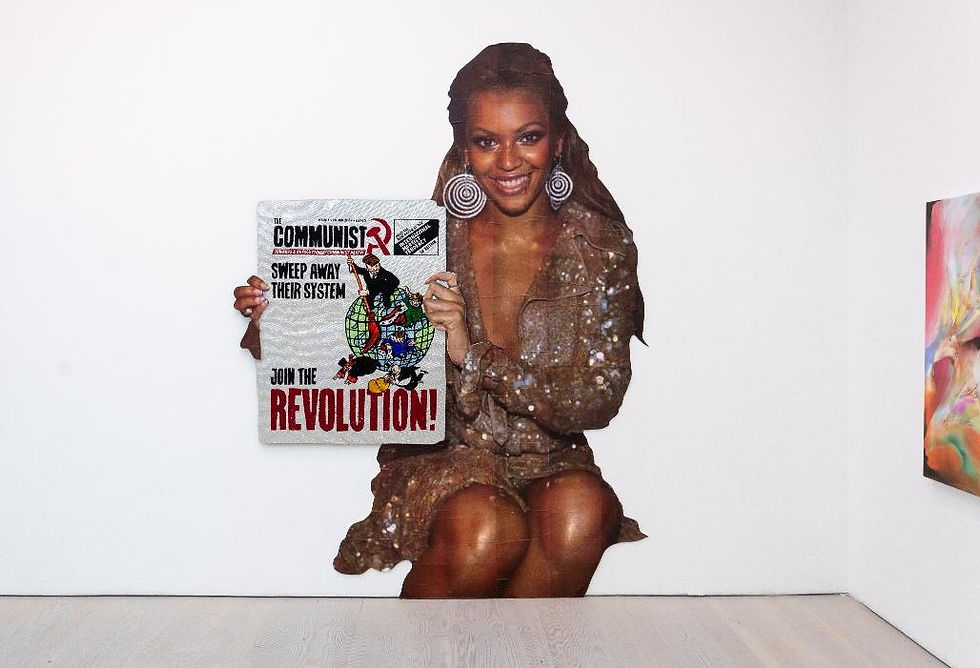

Kaari Upson, 156, 2013

Larry is both ridiculous and tragic, the object of both mockery and longing. This ‘both/and’ tension - irony and sincerity, critique and care - is what theorists Timotheus Vermeulen and Robin Van den Akker coined as metamodernism. A relatively new term, it describes a cultural mood of oscillation, rather than resolution, the idea of moving back and forth between concepts like hope and melancholy, unity and plurality, and, (as in the case of The Larry Project), sincerity and irony. Whether this marks a true shift beyond postmodernism, or simply the postmodern coming to terms with its own exhaustion, remains open - perhaps even part of the point.

S. Y. Her, The Revised Quadrant Model, 2016 (via The Philosopher's Meme)

Upson’s practice seems to embody this swing. Her sagging latex staircases, deflated chandeliers, and carpets crawling onto walls are at once grotesque and tender. Half organs, half furniture - they point to the impossibility of separating body from home, memory from fantasy, fragments of reality from half-imagined intimacy. Seen through that lens, House to Body Shift feels eerily at home in our moment - one defined less by irony or sincerity than by a restless oscillation between the two. The works, originally born from the ruins of American suburbia, now appear strangely prophetic within London’s art world of 2025: bold, hyper-mediated, perpetually caught between detachment and yearning.

Kaari Upson,Untitled (Kiss), 2008

Upson’s earlier Kiss Paintings (2008) perhaps distill this logic of doubling to its most literal form. She painted herself on one panel, Larry on another, then pressed them together while the paint was still wet. The result: two blurred, mirrored faces, neither whole, each contaminated by the other. It’s hard not to read this gesture now as an early sketch of our current cultural self-portrait; smeared between self and other, reality and representation, candidness and simulation. In Upson’s hands and filtered through her voyeuristic female gaze, the domestic seems to become a stage for this metamodern ambivalence: the desire to connect and to feel something real, even when every surface is traced with artificiality.

Kaari Upson,Internal Pocket 2, 2011

Is this why her retrospective lands so sharply now? After recovering from the yearly post-Frieze Week, there’s still just enough time to see House to Body Shift - to decide whether it feels more grotesque or tender, or indeed oscillates somewhat in-between. The show runs until November 1st, and offers a kind of quiet counterpoint to the art world’s noise: a space where longing and critique slowly melt into one another. Step inside, find yourself somewhere between voyeurism and care, and maybe let the silicone furniture stare back at you.