MAKIKO HARRIS'S 'LACQUERED REBELLION' AT KRISTIN HJELLEGJERDE

- Zoe Goetzmann

- Sep 19, 2024

- 5 min read

Arts writer and podcaster Zoe Goeztmann talks to artist Makiko Harris about her latest exhibition, Lacquered Rebellion at Kristin Hjellegjerde Gallery, exploring concepts of feminism, heritage, and the ambiguities of the shared experience of womanhood.

Photography courtesy of BJ Deakin/Kristin Hjellegjerde Gallery

Makiko Harris is a biracial, Japanese-American interdisciplinary woman artist. She holds a Bachelor’s Degree in Philosophy and Studio Art from Tufts University. She is a recent graduate from The Royal College of Art where she received a Master’s Degree in Contemporary Art Practice: Critical Practice. She has exhibited internationally in solo and group exhibitions in the United States, United Kingdom, Vienna and Japan.

Harris’s solo exhibition, Lacquered Rebellion at Kristin Hjellegjerde Gallery, consists of a series of sculptures and mixed media paintings created by the artist to explore the ambiguities surrounding contemporary feminism. The exhibition originated from her Needle series: on the passing of Makiko's grandmother from her Japanese family’s side, Harris received a sewing kit belonging to this family member. The artist recalls her grandmother’s sewing skills. To produce Makiko's series, Harris used welding to produce enlarged “needle” sculptures which, as she explains, are “powder coated.”

“To me, it seemed like a really important form of creative self expression to [my grandmother], coming from my quite westernised view of what it means to have freedom and agency in my own life,” Makiko continues, “she never went to school beyond 14. She didn't choose who she married. She didn't choose whether or not she was going to have children. You know, it's not that it was unusual for women of that time, but, she had literally no choice in her life. Coming from my perspective,” Harris remarks, “this [sewing] was one area where she was super creative.”

Textile art has made a recent resurgence throughout the London landscape. This year, the Barbican’s exhibition Unravel: The Power & Politics of Textiles in Art presented a retrospective on textile art and on gender. Included were works by Sheila Hicks, a female artist who revolutionised the domestic stereotypes surrounding textile-making through immense textile installations. In her review of the exhibition, Lauren Elkin wrote: “Perhaps [textile art is] a product of the renewed interest in the stories and art-making of women and other marginalised people, a way to feminize and decolonize the gallery space, to ask questions about labour and exploitation, about climate and extraction. More likely, it’s some combination of these factors, intertwined, impossible to separate.”

“My mother’s Japanese and my father is American,” she notes, “I was taught that in order to be powerful, I had to be masculine.” She continues: “I had to be a tomboy,” the artist says, “I had to [...] not care about things like my self-presentation,” Makiko recalls further, “because they are considered frivolous.” Lacquered Rebellion adds a layer to contemporary feminist discussions. Through artistic re-constructions of her grandmother’s sewing tools - the artist looks at the “subservient” position of Asian women through which they are “socialised,” she states, by the rest of the world.

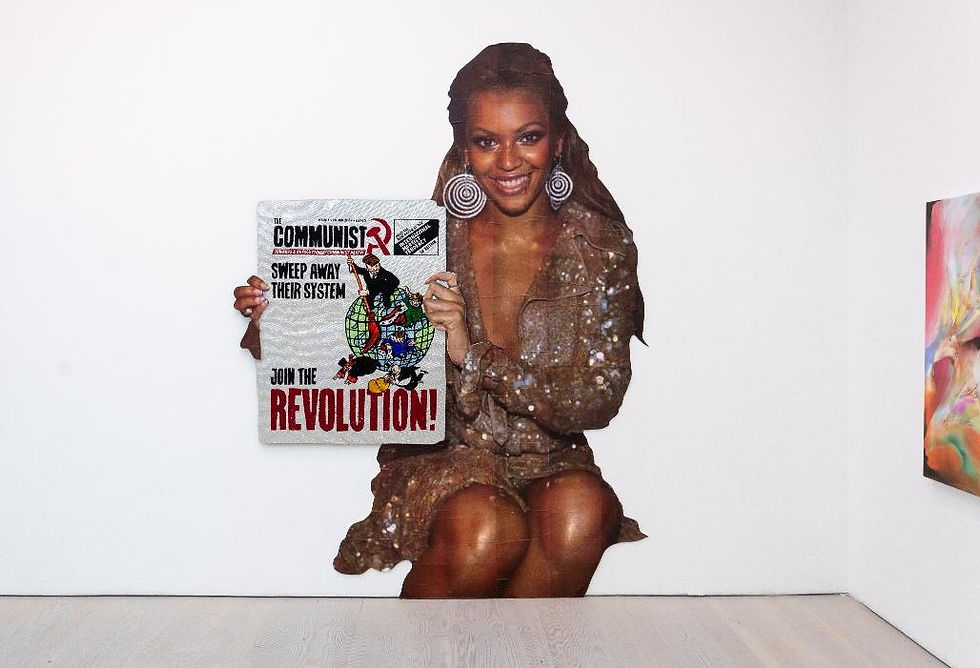

Through artistic, sculptural motifs of oversized needles, chains, lacquered red and silver nails (some seen gripping onto to medium to large-scale, abstract mixed-media paintings) as well as small, abstract paintings of female figures in fishnet stockings encased in aluminium material, Makiko transforms ordinary female “tools” into “weapons,” the artist explains. Harris explores the notions of “identity, femininity and the ideas of belonging,” as Kristin Hjellegerde notes, to subvert these traditional feminine (and fetishist) images into powerful objects.

Photography courtesy of BJ DeakinKristin Hjellegjerde Gallery

“Our generation,” Makiko says, “[has] a lot more agency and voice than perhaps what I witnessed [from] my grandmother.” Harris observes, “At the same time, maybe we need weapons to protect [us],” she reveals, “With Roe [v. Wade] getting overturned, I feel like sometimes, feminism has to be militant.” The artist continues: “There’s not necessarily [...] a softness and [...] we can’t necessarily relax into it.” As women, we are multidisciplinary individuals in this world (and art world). Considering United States history, Lacquered Rebellion could not have taken place at a more opportune time with the ongoing Presidential campaign, where women's issues have been featured from and centre by media.

When asked about the future of women artists, Makiko notes she adopts the perspective of intersectional feminism. She remarks: “We’re just part of the Zeitgeist. Some women artists are going to make work about their subjective experience[s] of being a woman, and some of them are not, and it’s not going to matter, you know?” Makiko adds, “My work isn’t really talking about how women artists need to be more represented, but they do.” By creating larger-than-life mixed media paintings and sculptures (or more intimate works), the exhibition serves as a reminder that women possess the power to take up both public and private spaces.

Near the end of our interview, Makiko and I mused over the question: “What are you?” - a (rude) phrase that had been asked repeatedly of both of us throughout our lives by people looking to determine our identities. Growing up, I would describe my childhood as being raised in an “idyllic bubble” - having the freedom to choose my future, not limited by my race or by my gender. Similar to Makiko’s grandmother, my grandmother, Natsue (Nakagawa) Masuoka was an expert seamstress. Every time I visit my childhood home, I survey her talents - looking at her immense quilts and intricate needlepoint Christmas ornaments she designed and made herself. I wish her art received public recognition.

Whilst I asked Makiko if she could share any feminist theories that inspired the creation of Lacquered Rebellion, I realised that the beauty of womanhood lies in the ambiguities and grey areas when it comes to understanding this topic.

Photography courtesy of BJ Deakin

“Do we have to be given [power],” Makiko asks, “or can we just take it?” She adds, “My key line is, liberation looks different for everybody.” The beauty of Lacquered Rebellion resides in the exploration of ambiguities, mysteries and multi-definitions of women: We are angry, we are powerful, we are shy — we are vocalising all these emotions to the world through Art created by marginalised artists, especially.

I remark to Makiko that our ambiguous statuses are “not an answer” to end racism: our identities provide us with semblances of freedoms to exist in two worlds. Through art (and writing), these creative forms allow new, unique, authentic ideas and voices to emerge in our surroundings [which Lacquered Rebellion captures accurately]. Building on the contemporary likes of Harris and Hicks, we represent necessary threads in the fabric of life (and the art world) integral to continuing the legacies of our (maternal) ancestors.

Lacquered Rebellion runs from 23 August - 21 September 2024 at Kristin Hjellegjerde Gallery, 36 Tanner Street London SE1 3LD

Zoë Goetzmann is an arts writer and podcaster based in London.