"THERE IS BARELY A DIVIDE BETWEEN MY INNER AND OUTER WORLD": PENNY GORING ON THE FEAR-FUELLED FANTASIA OF HER ART

- Agnès Houghton-Boyle

- Feb 7, 2024

- 9 min read

Penny Goring’s expansive practice is underscored by an uncompromising candour. The London-based artist and subject of a major retrospective at the ICA in 2022 makes work compulsively, instinctively and freely across mediums and in response to the contemporary state of emergency. Searingly honest poetry and references to history and culture are weaved throughout her semi-autobiographical paintings, drawings, sculptures and digital collages as a means to process personal experiences with trauma and depression, poverty and austerity. In a dark visual language that Penny has been developing since the 1980s she continually returns to the female form with violently charged, child-like scribbles and headless velveteen-pincushion dolls. During the 2010s, Penny garnered a cult-status in the online alt-lit scene for her image macros (a type of meme format) which she uploaded to her Tumblr, Facebook and Twitter. Concerned with challenging the conditions of making and exhibiting, Penny works with materials cheaply available to her such as ball point pens, fabric and food dye – and free computer programmes such as Microsoft Paint. She is part of a formidable legacy of feminist artists doing so and her work is displayed in the current, first of its kind, landmark Women in Revolt exhibition at Tate.

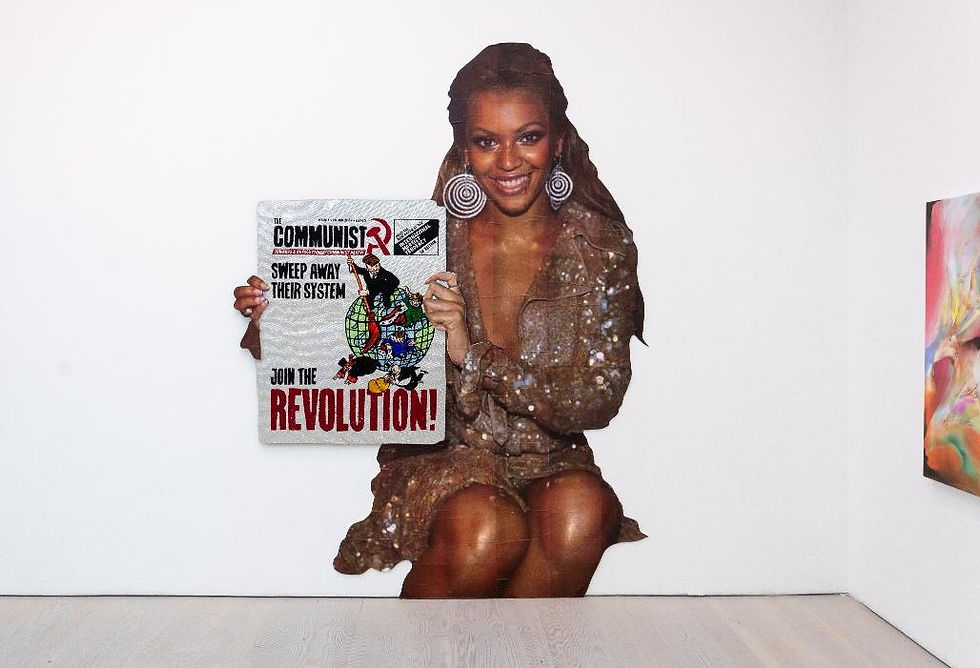

Installation view, PENNY WORLD, ICA, London, UK (2022) Image courtesy of Arcadia Missa.

You trained in Fine Art and Painting and went on to study critical fashion writing. Can you tell me about how your practice has developed?

Writing and art were always presented to me as two distinctly separate options but I wanted to do both. I struggled with this stupid binary for years. It wasn't until I merged them that I really got in my stride. On leaving school, I chose Fashion Writing, imagining it could incorporate both – but it absolutely could not. Then I did an art foundation course where it was recommended that I choose BA Illustration as a way to combine the two – which also proved totally inappropriate. Later, when doing BA Fine Art, it was at last the right area for me, but my writing was still a sideline. I was hindered by the strict divides imposed on my art practice and my writing practice – are you an artist or a writer? And even, are you a painter, or a sculptor, or a writer? – until I saw for myself that any and all disciplines can become one practice, and I began to explore the ways I wanted to combine everything. I didn't fully grasp this freedom until 2012.

Penny Goring, macro (you're desperate monster) (2017) via pgorig.tumblr.com

When did you decide to start making work for the internet and what was the reception of it?

In 2009 I began tweeting lines from my writing, and was invited to join an online writer's collective with its website where we posted our latest efforts. It was fab to give and receive constant feedback after working in solitude since graduating in 1994. People told me I was writing poetry, that I used words fearlessly, like paint, and for a few years I felt invigorated. By 2011 it bored me to be focused only on writing. Luckily I found Alt Lit, an online poetry community that seemed like a cool and mysterious secret gang – and it was humbling, because they were gleefully ignoring the binaries I'd struggled with – their approach was new, succinct, rebellious – suddenly my words seemed too wordy. I began honing my poetry, and making image macros, which are a way of making poetry visual that I first saw being done in Alt Lit, and I became obsessed with making them, it was a magic way to manipulate words and images into one work. This led me to non-stop making and posting online – the internet gave me the tools to make everything I'd ever tried to imagine: poetry was in everything, anything was art, nothing was art, who cares, not me: liberated from the constraints of academia and the art world, I made countless image macros, gifs, video- poems, began using my voice, my face, and then I began to incorporate drawing, painting, sculpture too – it all came together seamlessly.

Your drawings, paintings, sculptures, videos and poetry are about things that you have dealt with in your life. They are about personal experiences of pain, violence, addiction, poverty and loss, and respond to a deep sense of injustice. How do you channel uncomfortable feelings, the distress, rage and pain, into your making process?

There is barely a divide between my inner and outer world, this makes it easy for me to confront my feelings and use them. It starts in my sketchbooks/diaries, where I write and draw everything I'm thinking or feel like saying or making, or simply rant and doodle, even stuff I'd never say or do, whatever. If I'm alone at my work table with hand, eye, brain engaged, the emotions that I need to communicate lead to the decisions involved in making the work, and this process causes the momentum, it's like rolling a ball. Sitting with the feeling will conceive the idea, deciding how to do it gets it done.

When did you develop Amelia as your alter-ego?

Amelia is a dead junky, a gifted photographer, useless at life, friends used to say, 'she's away with the fairies', I identified with that – we were together until I got sober and she didn't. She got into heroin and overdosed several years later. It shook me. She first appeared in my work as subject matter in 2016 – I made a sculpture for her called Pyre (2016), which has recently been acquired for Tate Britain's permanent collection, it's a pile of logs- limbs made from a variety of black fabric, including velveteen, fake fur and PVC, some embroidered with words, such as: 'IF U WAS EVER ALIVE - IF I WAS EVER DIRT'.

Penny Goring, Emotive title (Super virilent hyperdeath virus targeted at you know whose) (2017), Amelia Makes The Rain (2017), Pyre (2016)

Image courtesy Arcadia Missa/Tim Bowditch

In 2017 I started making the Amelia drawings because she was still on my mind. Rather than exorcising her, Pyre (2016) had brought her closer. I drew us as twins, a double-sided coin, turned us into iconic mythical characters. I didn't dramatise, no need, I freeze-framed and glamorised certain moments, same as memory does, and put us in landscapes that reflect how it felt, not the suburbs we roamed but the hostile broken beauty of these never ending end times. The two figures are interchangeable, dead and alive, good and evil, stupid and wise, both equally capable of anything, self-destruction, violence, loving – the Amelia drawings and paintings tie us into archetypal tales, and exploit our doomed attempts to get lost in a world of our own making whilst actually being lost inside alcoholism inside this neo-liberal capitalist hellscape.

Penny Goring, Pyre (2016)

Your work arises out of a tradition of radical, punk and female art making. To look at your work is to see Hesse and Bourgeois in your sculpture and Acker in your splittingly direct writing. Were these women your influences?

I didn't study Art History until 1991, when I eagerly dived right in. My main influences are the books I read, films and TV shows, fashion and music. And always: my disgust with the world at large. Hesse and Bourgeois were two of the first artists I felt an affinity with, Bourgeois for her use of words, fabrics, (I'd been making fabric 'things' since childhood, never knew what they were, they had no use – oh wow, they're sculpture) and her unashamed use of autobiography, Hesse for her ability to suffuse abstract, minimal shapes with intense emotion, studying their work was helpful. But as for Acker, to this day, I have never read a word she wrote. I do know that she had many similar attitudes towards writing as I do and she often employed similar strategies. I also get compared to Sarah Kane, but I've never read any of her work either.

Talk to me about the bodies in your work: your ball point drawings of women, sisters, wives, friends, lovers, enemies, these spindly figures that envelop each other and do violence to one another. Your headless, fabric doll sculptures evoke plush voo-doo doll pin cushions. Why do you use the repeated image of the body? When did you start developing these figures?

I've been drawing self-portraits and imaginary people since I was a kid. I spent 4 years in life drawing classes. I've spent weeks drawing only hands. The body is all we've got, it's where we live and die, it houses us, it's our vehicle, it feels pain and pleasure, and it makes a multitude of great shapes that I can distort at will to convey feelings, yet still it will be recognised as a human body. Even an expressionless face is unique, but a headless doll is often more evocative, could convey distress, violence, grief or illness – so much stuff in this life can cause you to 'lose your head' – how about love? drugs? poverty? war? I prefer to leave the doors open for the viewer's individual interpretation, often reducing the body to its essential shapes until it becomes a signifier, ascends itself, says more.

Tell me more about repetition. What are you hoping to do with your doll series in which you remake the same figure over and again stitching in different, wryly anarchic word formations?

You're referring to the velvet Forever Dolls I made in 2023 for my Chronic Forevers show at Galerie Molitor, Berlin. Repetition allows for contradiction and variation within the same theme. I adore contradiction. I chose to make and install them in strict formation to form an army, a family, an infestation, together they are a cacophony, a chorus, apart each has its own particular message and mood. Twelve of the dolls are the exact same shape and size but the 13th is double size and has very long legs, placed centrally she seems like an avenging angel leading her host of love/death bringers, desperate lil' demons, forever in pain, flying towards futility.

From left to right: Penny Goring, Forgotten Doll (2019), Plague Doll (2019), Grief Doll (2019), Ghost Doll (2019), Black Forever Doll (2019), No Escape from Blood Castle, Installation view, (2021)

Can you tell me about symbols in your drawings? It reminds me of Acker and seems to perpetuate her tradition of mythmaking by weaving fable into personal history, imagination into history, humour into pain. Creating a strange terrifying alchemy.

The symbols come about naturally, develop, and continue to be meaningful to me over time, I don't question them. You could say they're like my own personal emoji. I prefer everything I've ever made, ever make, to be in dialogue, within the varying mediums I use it's always my take on the world, my symbols, my own invented language.

Tell me about the choice to use humour in your work.

It's not actually a conscious choice. It's just me being me. I don't flinch from hardly any subject or taboo and I hold nothing in reverence, I'm not polite, nothing is sacred, unless I say it is. Also, I'm being dead serious. I never intend to be humorous. I deliberately take honesty to extremes, until it becomes something else, expands and shatters, into fabrication, fear-fuelled fantasia, that's where the action is. Amongst other things, this process seems to generate something people apprehend as humour.

Penny World exhibition booklet, courtesy of ICA London

The Penny World show at the ICA was a major retrospective of your career over the past 30 years. What was your intention for the show?

I was lucky to work with an incredible curator, Rosalie Doubal, who has been familiar with my work for years. Our intention was to make the ICA galleries feel like they belonged to me. Also, I wanted to use every inch of the space by showing works at varying heights, and playing with scale, size, width, and texture – showing the Anxiety Objects by tying them to gym ropes hung from the lower gallery's central rafters was perfect as it meant we were also bisecting the space! We didn't show the work chronologically because I wanted to evoke crip time [a concept arising from disabled experience that addresses the ways that disabled/chronically ill and neurodivergent people experience time (and space) differently]. To create an unexpected moment of pause, we hung one small painting on velvet (from a series of 10 called Those Who Live Without Torment), all on its own in a hallway between the two upper galleries, with a bench in front of it, for people to sit down and breathe. I'm currently reading Susan Sontag's diaries where she quotes someone as saying something like: a retrospective is a disaster for a living artist because everything they make afterwards is posthumous. Penny World deliberately wasn't a retrospective, though it was widely received as such and that's fine - it wasn't exhaustive, we only showed selected aspects of my work, and only from a 30 year period, much of it was previously unseen, or only on the internet, or made in my treasured obscurity era only to be buried in my home studio.

Agnès Houghton-Boyle is a critic and programmer based in London. Her writing features in Talking Shorts Magazine and Fetch London.